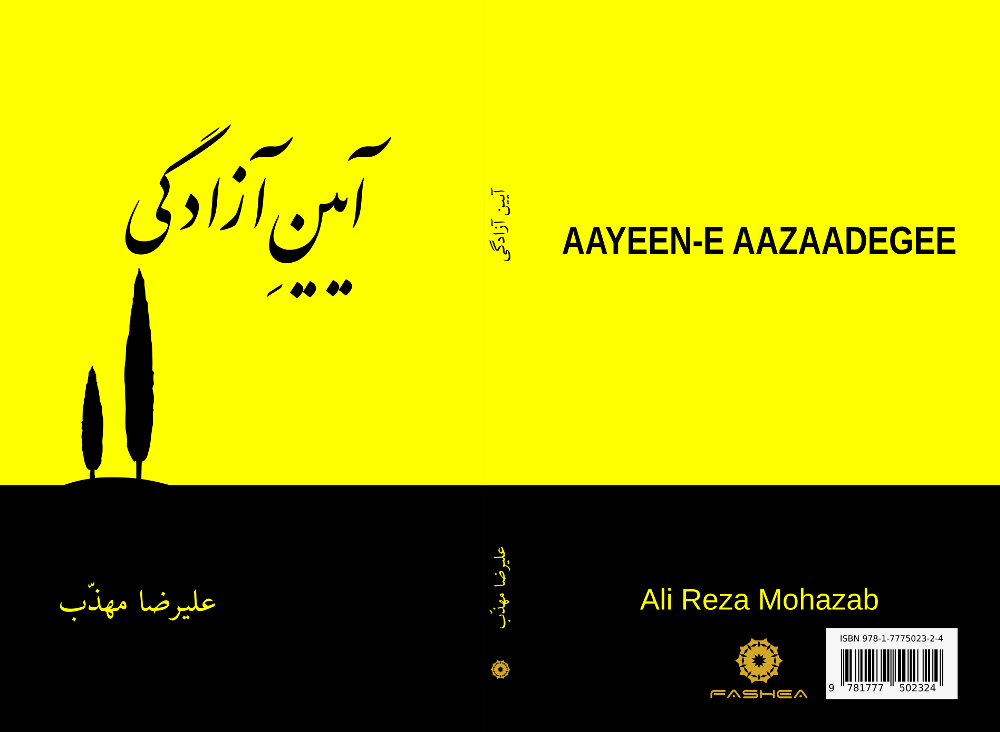

Aayeen-e Aazaadegee

| Title | آیین آزادگی [Aayeen-e Aazaadegee = The Mores of Liberality] |

|---|---|

| Author | علیرضا مهذب [Ali Reza Mohazab] |

| Language | Persian (fa) |

| Print Length | 116 pages |

| Publication Date | 2021-12-31 |

| ISBN | 978-1-7775023-2-4 (Paperback) 978-1-7775023-3-1 (PDF) |

| Size | US-Trade 6"x9" |

| Price (PDF Format) | $3.44 (CAD) |

> About the book:

Aayeen-e Aazaadegee (translating to The Mores of Liberality) is a concise book in Persian, by Ali Reza Mohazab, on libertarian ethics, in the Rothbardian tradition. The book is the sequel to the earlier work of the author, Konesh-Naameh (translating to The Book of Action), on Austrian Economics. Whereas Economics itself is a value-free science, its exercise cannot be decoupled from an ethical system that addresses the questions of property rights and justice. So the book sets to develop the ethics required to be respected by the majority of the citizens of an anarcho-libertarian society — an absolutely free market society.

The foundation of the ethical system that The Mores of Liberality expounds, lies in the recognition of the absolute self-ownership of the human beings, coupled with the non-aggression principle. It is further seen that other "human rights" are only valid and acceptable as special cases of property rights. To drive the point home, several ethical issues are further examined through the prism of self-ownership and property rights, and the libertarian stance on the issues is explained and justified.

In a later chapter, the legitimacy of the entire concept of the state is examined. It is concluded that the state, in the conventional sense, cannot exist without infringing on the property rights of the citizens, and therefore, its existence is immoral. Brief explanations are given on the causes behind the perpetuation of the states in the world and additionally some of the shortcomings of democracies are enumerated.

In the final chapter, the issues of Justice, restitution and punishment are briefly explored and some of the difficulties of administrating just punishments are explained. The book concludes with an exposition on contracts as conditional property transfers, and their enforceability.

The Mores of Liberality, like its prequel, is written in the language and style of early Modern Persian books of the tenth and eleventh centuries A.D., to be understood and to be appreciated by the readers of that particular era. There is, however, a fairly extensive preface, aimed at the contemporary readers, written in contemporary Persian. The preface, titled "A word with the contemporary reader", examines some of the references to liberty and liberality, in Persian literature, and in some of the works of Iranian thinkers on ethics and political theory. The preface further contextualizes the Rothbardian ethics in the broader framework of the classical liberal and libertarian thought of the 19th century and the early 20th century.

To call the conclusions of this book "radical", is not an exaggeration; It would be wishful thinking to expect a full-on conversion of the readers, to the libertarian creed upon reading this book. However, it is hoped that the readers of the book would develop a new appreciation for an ethical system which has an obsession with freedom and respecting the ownership rights of humans over their soul, body and property. At the very least, the book provides a fresh way to analyze the ethical problems, and matters of justice and tyranny.

We will never know how the public reception of the ideas expounded in this book would be in the 10th century Persia. As argued in the preface, however, the starting point of the book (self-ownership and non-agression) was well within the accepted norms of the population. It would then become a matter of being consistent in applying the principles, and leaving people alone as long as they are not infringing on others' just property.

This book would also provide the theoretical ammunition to scrutinize and criticize the actions of the state and then to deny its legitimacy, in a rational ethical framework based on intuitively acceptable axioms. In fact, after reading The Book of Action and The Mores of Liberality, the reader from a thousand years ago would be able to to go after the state, and to deny its legitimacy from an ethical perspective (the subject of this book), and to deny its necessity from an economical perspective (a natural conclusion from the previous book).

With regards to the questions of the necessity of the state, or the flip-side of the coin, the practicality of an anarcho-libertarian society, as discussed in the preface of the current book, there have been brief theoretical exercises in conceiving such society, The city of the free, in the works of Farabi. Unfortunately, the idea was never explored further by the political thinkers of the era. Nevertheless, one should keep in mind that the state played a far less prominent role in the lives of the population, compared to our times where every aspect of our living is thoroughly regulated and interfered by the state. In those times the actions of the states were manaces to be tolerated. Therefore, it would have been arguably a smaller intellectual leap, compared to our time, to imagine an anarcho-liberatarian society—provided that one could let go of the fear of the proliferation of heretic sects. Of course as a libertarian, one should not care about such proliferation, so long as no property rights are being infringed.

The legitimacy question of the state would in fact be more important than the practicality question, as the practical issues could be worked out, once one was armed with a proper economic and a proper ethical theory. In the eyes of the majority, the legitimacy of the king depended on divine blessing. However, at times, the rouse was completely exploded, and the naked nature of rulership, being reliant on coercion and violence, was exposed—as in the case of Yaghub Leith and the people of Nishapur. In fact, it was due to the coercive nature of the state that people like Abu Musa Mordar considered anyone who associates with the ruler, to be an infidel. So, as one can see the idea of the denial of the legitimacy of any state (not just one ruler vs another ruler) on ethical grounds was indeed around the corner. Unfortunately as far as we know, it was never materialized and in the subsequent centuries, history took a different turn.

While one would never know how the Iranians of the golden era, who called themselves the sons and daughters of the liberals, would adopt the mores of liberality, but it is certainly hoped that the Persian speakers of our time would enjoy reading this book and find it useful.

> دربارهٔ کتاب:

آیین آزادگی کتاب مختصریاست به قلم علیرضا مهذب در اخلاق لیبرتاریانی در سنت راتباردی. این کتاب در واقع ذیلیاست بر کتاب پیشین نویسنده، کنشنامه که در مبانی اقتصاد مکتب اتریش است. با آنکه اقتصاد علمیاست که ارزشگذاری نمیکند، به کاربستن آن بدون داشتن نظریهٔ اخلاقیای که به مسائل مربوط به عدالت و حقوق مالکیت بپردازد، میسر نیست. از این رو در این کتاب به تبیین نظام اخلاقیای که باید مورد تبعیت بیشتر اهالی جامعهای آنارکو-لیبرتاریانی — یعنی جامعهٔ بازار مطلقاً آزاد — باشد پرداخته شدهاست. نظام اخلاقیای که آیین آزادگی پی میافکند بر دو اصل کلی نهادهشدهاست: مالکیت مطلق انسانها بر جان و تن و دارایی خود، و دوم، عدم تعرض به مالکیت دیگران. در طول کتاب مشخص میشود که سایر «حقوق بشر» تنها هنگامی معتبر و پذیرفتنیاست که حالت خاصی از حقوق مالکیت باشد. در این کتاب برای تفهیم هرچه بیشتر این امر، چندین مسئلهٔ اخلاقی با عینک عنایت به حق مالکیت بر هستی و دارایی خود بررسی شدهاست و مواضع منتسب به آزادگان توضیح داده شده و توجیه گشتهاست.

در گفتاری متأخرتر، مشروعیت حکومت در کلیت آن بررسی شدهاست و نتیجه گرفته شدهاست که از آنجا که حکومت، در معنای متعارف آن، بدون نقض حقوق مالکیت شهروندان نمیتواند وجود داشته باشد، وجودش غیراخلاقیاست. به علاوه توضیحاتی در علل تداوم حکومتها در جهان بیرون آورده شدهاست و نیز برخی کاستیهای نظامهای دموکراتیک برشمرده شدهاست.

در واپسین گفتار کتاب، به مسئلهٔ عدالت، اعاده، و مجازات به طور خلاصه پرداخته شدهاست و برخی دشواریهای نظری در صدور حکم مجازات عادلانه بیان شدهاست. کتاب با توضیحی دربارهٔ قراردادها به عنوان وسایلی برای انتقال شرطی مالکیت و نیز توضیحاتی دربارهٔ به اجرا گذاشتن آنها پایان مییابد.

آیین آزادگی، همچو کتاب پیشین نویسنده، به نثر مرسل دورهٔ تکوین فارسی دری — یعنی قرنهای چهارم و پنجم هجری قمری — نوشته شدهاست و مخاطبش فارسیزبانان آن عصرند. با این حال، کتاب حاوی پیشگفتاری نسبتاً مفصل با عنوان سخنی با خوانندهٔ امروزی است که در آن به نثر امروزی فارسی به بررسی مفهوم آزادی و آزادگی در ادبیات فارسی و آثار اخلاقی و سیاسی متفکران ایرانی میپردازد. علاوه بر این، نویسنده در این پیشگفتار جایگاه نظام اخلاق راتباردی را در بستر تفکرات و تحولات قرن نوزدهم و اوایل قرن بیستم میلادی در مغرب زمین به دست میدهد.

اگر بگوییم که مطالب و نتایج آمده در این کتاب «رادیکال» است اغراق نکردهایم. وانگهی خوشخیالی محض است اگر انتظار داشته باشیم که خوانندگان پس از خواندن کتاب با تمام وجود به مرام آزادگی یا لیبرتاریانیسم بگروند. ولی شاید بتوان امیدوار بود که پس از خواندن این کتاب با مرام آزادگی — که تا حد وسواس به مالکیت انسانها بر هستی و اموالشان احترام میگذارد — بیشتر همدلی کنند. هر چه باشد، این کتاب دستکم شیوهای جدید برای نگریستن در مسائل اخلاقی و امور مربوط با عدالت و ظلم به دست میدهد.

هرگز نخواهیم دانست که برخورد عموم خوانندگان سدههای زرین تاریخ ایران با این کتاب چگونه میبود. ولی، چنان که در پیشگفتار کتاب آمدهاست، نقطهٔ آغاز این کتاب (یعنی حق مالکیت و اصل عدم تعرض) برای مردمان آن عصر به هیچ روی بیگانه و خلاف هنجار نمیبود. فقط باقی میماند اعمال و به کار بستن این اصول و اجتناب از نقض آنها — یعنی اینکه مردمان را تا هنگامی که متعرض مالکیت برحق دیگران نشدهاند به حال خود باز گذاشت.

علاوه بر این، آیین آزادگی حربهٔ نظری لازم را — بر پایهٔ یک نظام اخلاقی خردمحور با اصولی فطرتاً پذیرفتنی— برای مداقه و نقد اعمال حکومت و سپس نفی مشروعیت حکومت به دست میداد. در واقع خوانندهٔ هزار سال پیش، پس از خواندن کنشنامه و آیین آزادگی قادر بود که لبهٔ تیز حملات نظریاش را متوجه نهاد حکومت کند و مشروعیت آن را از دید اخلاقی (نتیجهگیری این کتاب) و ضرورت آن را از دید اقتصادی (با توجه به محتوای کنشنامه) نفی کند.

در مسئلهٔ مربوط به ضرورت وجود حکومت، یعنی ناگزیری از آن یا روی دیگر سکه، یعنی امکان برپا داشتن جامعهای آنارکو-لیبرتاریانی، چنان که در پیشگفتار کتاب حاضر آمدهاست، فعالیتهای نظری مختصری در سدههای زرین صورت گرفته بود. با این تفصیل که ابونصر فارابی در آثارش جامعهای لیبرتاریانی مبتنی بر آزادی حداکثری افراد را (مدینهٔ احرار) از دیدگاه نظری تصور کرده بود و برخی ویژگیهای آن را به طرزی شگفتانگیز بیان کرده بود . ولی متأسفانه دنبالهٔ کار هرگز گرفته نشد. به این نکته هم باید توجه کرد که حکومت در آن عصر حضوری کمرنگتر در امور روزمرهٔ مردم داشت و مانند امروز نبود که در جزئیترین جنبههای زندگی افراد دخالت و ضابطهگذاری کند. بیشتر مردم اعمال حکومت را به چشم مزاحمتی میدیدند که باید تحمل میشد. بنابراین شاید بتوان ادعا کرد که از لحاظ نظری تصور جامعهای بدون حکومت نیاز به جهش فکری کمتری نسبت به امروز داشت — البته به شرطی که شخص (مومن) میتوانست بر نگرانیاش از شیوع زندقه غلبه کند. مسلماً اگر کسی آزاده میبود تا هنگامی که زنادقه متعرض حقوق مالکیت دیگران نمیشدند غم به دل راه نمیداد.

وانگهی مسئلهٔ مربوط به مشروعیت حکومت مهمتر از مسئلهٔ ضرورت حکومت یا به تعبیر دیگر عملیبودن مدینهٔ احرار است. چرا که هنگامی که به حربهٔ نظری علم اقتصاد و نظریهٔ اخلاق آزادگی مسلح باشیم میتوانیم به مصاف مسائل عملی برویم. در چشم بیشتر مردم مشروعیت حاکم مبتنی بر تأیید الهی بود. ولی در مواقعی—مثلاً در قضیهٔ یعقوب لیث و مردم نیشابور— بطلان این نیرنگ آشکار میشد و سرشت عریان حکومت که مبتنی بر اعمال زور و ضربت شمشیر بود، عیان میگشت. فیالواقع به سبب همین سرشت زورگویانهٔ حکومت، کسانی چون ابوموسی مردار هرکسی را که با سلطان اختلاط کند کافر میدانستند. چنان که دیده میشود، تا ایدهٔ نفی مشروعیت هرگونه حکومت (نه این حاکم در مقابل آن حاکم) از دیدی اخلاقی یک منزل بیشتر فاصله نبود. تا آنجا که میدانیم کسی به این منزل واپسین نرسید و در سدههای پس از آن، درِ تاریخ بر پاشنهٔ دیگری چرخید.

هرچند هرگز نمیتوان دانست که آیین آزادگی چه اندازه نزد ایرانیان سدههای زرین که خود را فرزندان آزادگان میخواندند، مقبول میافتاد، میتوان امیدوار بود که این کتاب مورد قبول پارسیزبانان این عصر قرار گیرد و از خواندن آن لذت و فایده برند.

اگر قادر یا مایل به استفاده از خدمات پیپَل

نیستید، میتوانید درخواستی به

نشانی