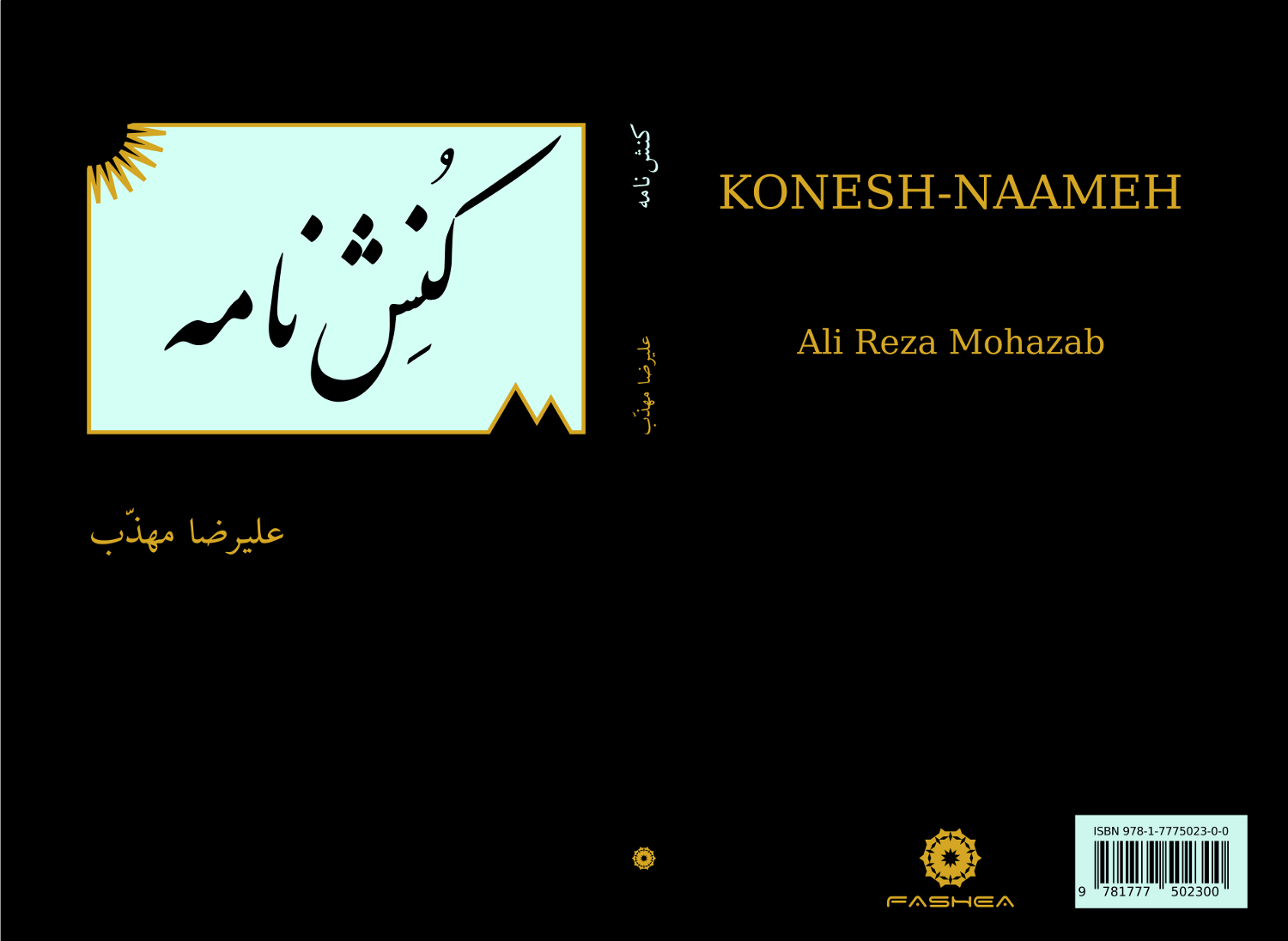

Konesh-Naameh

| Title | کنشنامه [Konesh-Naameh = The Book of Action] |

|---|---|

| Author | علیرضا مهذب [Ali Reza Mohazab] |

| Language | Persian (fa) |

| Print Length | 156 pages |

| Publication Date | 2020-12-15 |

| ISBN | 978-1-7775023-0-0 (Hard Copy) 978-1-7775023-1-7 (PDF) |

| Size | US-Trade 6"x9" |

| Price (PDF Format) | $3.99 (CAD) |

> About the book:

Konesh-Naameh which translates to "The Book of Action" in English, is an introductory book on Economics in the Austrian School tradition, as expounded by Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973) and his disciple Murray N. Rothbard (1926–1995). Following the method and footsteps of these great economists, the author, Ali Reza Mohazab, starts from the fundamental concept of Human Action and derives all the major laws of Economics, such as that of supply and demand, in a logical step by step fashion. In the later chapters of the book, the author proceeds to discuss the ramifications and applications of such laws in a free market economy, as well as one hampered by the state interventions.

The book is written in Persian, in the archaic style of the prose of the early Modern Persian scientific works, from the tenth and eleventh century AD. For the English speakers, perhaps one can use the the analogy of writing in the style and language of Geneva Bible (written in the 16th century AD). As the author puts it, the book is written in such a way that if the thousand-year-old dead are resurrected, they will be able to understand what is written. It has been the intention of the author to point out the maturity and the capacity of the Persian prose of that era to deliver the modern and intricate ideas of the social sciences as developed in the twentieth century.

Of course, the current advanced state of the science of Economics, and in particular that of the Austrian School Economics, is the result of the intellectual labour of numerous western thinkers of great calibre throughout many centuries. However, if the the historical development of the social sciences had taken another route, in such a way that these principles of Economics were first developed in the Persian-speaking world during the golden era of the 9th to 11th century AD., one might speculate that what might have been written down in a book, would not be too different from the current work.

Such speculation is implicitly asserting that thinking about, and developing the fundamental concepts of Economics, does not require extraordinary advances in other branches of sciences such as Physics and Chemistry, or even Mathematics. Neither does it require extraordinary technological advancements, let alone an industrial revolution. This book is a clear testament to this assertion, and shows that the late appearance of Economics, as its own branch of science, is more of a historical accident, than a historical necessity.

The examples in this book, as well as the way the dates, numbers, and measurement units are expressed, are in accordance with the atmosphere and the level of technology during that golden period of the Persian history. In one instance, however, when the author is speaking of money printing and inflation, he references incidents from the period in which Persia was under the Mongol rule (13th Century AD). Logically, the readers from a thousand years ago, were not aware of the catastrophes of the Mongol invasion which would happen centuries later. However, the way the author refers to the events is as if he is discussing the events of a distant past (say in the Sassanian era) or perhaps the events pertaining to the reign of some obscure local rulers. As such, there would be no barrier in understanding for the supposed thousand-year-old readers.

The love and interest of the author in Persians and the Persian language is evident throughout the book, in particular in the introduction. For example, the author has dedicated the book to the soul of Reyhanah the daughter of Hossein of Chorasmia, and all those who have yearned for the delivery of sciences in Persian. Reyhanah is of course the dedicatee of one of the earliest and greatest works of Mathematics and Astronomy in Modern Persian, Al-Tafheem Le-Avaaele Sanaa'ate Al-Tanjeem, written by the Persian mathematician and scholar Al-Birouni (973–1048 AD). Al-Tafheem, with its full name translating to "The Exposition on the Basics of the Art of Astronomy", is the only extant work of Birouni which is written in Persian, as the majority of his works were written in the lingua franca of the time, Arabic. Had it not been for the interest of the young lady in Astronomy, the book Tafheem would have never been written. Thus the Persian language would have been deprived of an invaluable gem. It seems that our author would have wanted the young Chorasmian lady to learn about the principles of Economics after learning the basics of Arithmetic from the book Tafheem.

Another Persian book, that the author of Konesh-Naameh, specifically mentions in his introduction, is Daanesh-Naameye 'Alaayi by the Persian polymath Avicenna (980–1037 AD). This encyclopedic work whose name translates to "Alayid Book of Science" or "Alayid Encyclopedia", was written by the request of a local ruler, Ala'oddowlah, who was the patron of Avicenna. To elaborate, Ala'oddowlah asked the great polymath to write a book in which the philosophical and natural sciences are explained in Persian, so that Ala'oddowlah and the people at his court who did not know Arabic, could still benefit. And thus a great service was rendered to the Persian Language and the tradition of scientific writing in Persian

The reference to Alayid Encyclopedia, in Konesh-Naameh, is important from another aspect as well. As we know Avicenna was one of the greatest Aristotelian philosophers of all time, and built extensively on the ideas of the Greek philosopher. Avicenna's philosophical works found their way into Europe through translations, and had a major intellectual influence on the scholastic philosophers, such as Albert the Great, and Thomas Aquinas. Interestingly enough, Murray Rothbard, the great economist and philosopher of the Austrian school, himself was deeply influenced by Thomas Aquinas, and was clearly Aristotelian in his philosophical argumentation and exposition style. Therefore, his ideas fit well in the framework of Avicenna philosophy. The author of Konesh-Naameh, being aware of this fact, categorizes the sciences into the two major branches of theoretical and praxeological in accordance to Avicenna (and other Aristotelians) in the first step. He, then, augments such categorization with the Rothbard's categorization of the sciences of human action.

One can detect traces of the style and language of many Persian works of that era (besides Al-Tafheem and the Alayid Encyclopedia) woven into the fabric of the current text. Examples include the other Persian works of Avicenna, and those of his disciples as well as numerous books on Geography, Mathematics, Astronomy, History, Theology, Religion, Logic, Ethics, and Statesmanship by various authors of different creeds.

It is hoped that the students of Economics and those with an interest in Persian literature will find the book useful and a joy to read.

> دربارهٔ کتاب:

کنشنامه کتابی است در مبانی اقتصادِ مکتبِ اتریش بدانگونه که توسطِ دو اقتصاددانِ بزرگِ این مکتب، یعنی لودویگ فُن میزس (۱۸۸۱–۱۹۷۳م) و موری نیوتن راتبارد (۱۹۲۶–۱۹۹۵م)، پیریزی و شرحو بسط داده شدهاست. نویسنده، به پیروی از این دو اقتصاددان، از مفهومِ بنیادینِ کنش و چند اصلِ بدیهی آغاز میکند، و قدم به قدم اصول و قوانینِ علمِ اقتصاد را از آنها استخراج میکند. در بخشهای بعدی کتاب، کاربردِ قوانینِ اقتصاد، از جمله قانونِ عرضه و تقاضا و نهاده شدنِ قیمتها و نرخِ بهره را در جامعهٔ بازارِ آزاد و نیز در جامعهای که حکومت در امورِ اقتصادی مداخله میکند، شرح میدهد.

سبکِ نثرِ کنشنامه تقلیدیاست از نثرِ مرسلِ کتابهای علمی فارسی در سدههای چهارم و پنجم هجری قمری. به قولِ نویسنده، نثرِ کتاب به شیوهای است که اگر مردگانِ هزار ساله سر از خاک بر آورند، قادر به درکِ سخن باشند. نویسنده بدین وسیله خواستهاست که پختگی و آمادگی نثرِ فارسی آن دوره را برای بیان مفاهیمِ دقیق و باریکِ علومِ انسانی در دورانِ معاصر نشان دهد.

مسلم است که این درجه از کمال و پیشرفت در علمِ اقتصاد، بهخصوص اقتصادِ مکتبِ اتریش، که امروز شاهد آنیم، حاصلِ تفکر و فعالیتِ علمی عدهٔ پرشماری از دانشمندان و نوابغ مغربزمین در طی صدها سال است. با این حال، شاید بیراه نباشد اگر بگوییم که چنانچه روندِ تاریخی تکاملِ علم به گونهای دیگر میبود، و این مفاهیمِ اقتصادی اولین بار توسطِ دانشمندان فارسیزبانِ ایرانی در قرن پنجمِ هجری قمری اندیشیده میشد، و از ذهنِ ایشان تراوش میکرد، حاصلِ کار بیشباهت به این کتاب نمیشد. این ادعا متضمن این نکته هم هست که درک و اندیشیدن به مفاهیم بنیادی اقتصاد، نیازمندِ پیشرفت خارقالعادهٔ علومِ دیگر نظیرِ فیزیک و شیمی و حتی ریاضیات، یا دستاوردهای تکنولوژیک و وقوعِ انقلاب صنعتی نیست. این کتاب شاهدی روشن بر این مدعاست و نشان میدهد که ظهور و پیشرفتِ دیرهنگامِ علمِ اقتصاد، به معنای امروزی آن، یک اتفاقِ تاریخی بودهاست و نه یک ضرورتِ تاریخی.

مثالهای کتابِ حاضر، و طرز بیان تاریخها و اعداد و واحدهای اندازهگیری، همه منطبق با حال و هوا و سطح دانش و تکنولوژی سدههای طلایی تاریخ ایران (قرنهای سوم تا پنجم هجری) است. البته در یک مورد، که نویسنده از چاپ اسکناس و تورم سخن میگوید، در مثالی، اشاره به وقایعی در عصر ایلخانی (سدهٔ هفتم هجری) میکند. گرچه خوانندهٔ هزارسال پیش علیالاصول از فجایعِ عهد مغول که صدها سال پس از وی رخ دادهاست، بیاطلاع میباشد، اشاره و توضیحِ نویسنده به گونهایاست که در فهمِ مطلب برای خوانندهٔ هزارسال پیش مشکلی ایجاد نمیشود، و انگار که به وقایعِ دوران ساسانی اشاره شدهاست، یا از خاندانی محلی سخن رفتهاست.

علاقه و دلبستگی نویسنده به ایرانیان و زبان فارسی در جایجای اثر، خصوصاً در دیباچهٔ آن، موج میزند. از جمله اینکه کتاب را به روانِ ریحانه دختر حسین خوارزمی و دیگر کسانی که خواستار عرضهٔ علوم به زبان فارسی بودهاند، تقدیم کردهاست. ریحانه همان کسیاست که ابوریحان بیرونی تحریر فارسی کتاب تفهیم (با نام کامل التفهیم لاوائل صناعة التنجیم) را که در مقدمات علم نجوم است و تنها اثر فارسی ابوریحان است برای وی نوشتهاست. اگر علاقهمندی این دختر خانم به علم نجوم نمیبود، شاید کتاب تفهیم، آن هم به فارسی، هرگز نوشته نمیشد و زبان و ادبِ فارسی از گوهری گرانبها بیبهره میماند. به نظر میرسد که نویسندهٔ ما هم خواستهاست تا این دختر خانمِ خوارزمی، پس از آموختنِ مبانیِ علم حساب از کتاب تفهیم، با مبانی علم اقتصاد هم آشنا شود.

علاوه بر تفهیم، کتابِ دیگری که نویسندهٔ کنشنامهٔ حاضر به طور خاص از آن در دیباچه نام میبرد، دانشنامهٔ علایی شیخ الرئیس ابوعلی سیناست. این اثرِ گرانقدر چنان که میدانیم به خواهشِ علاءالدوله کاکویه نوشته شد؛ با این تفصیل که علاءالدوله از بوعلی درخواست کرد که کتابی بنویسد که در آن علومِ فلسفی به زبان فارسی بیان شده باشد، تا علاءالدوله و اطرافیان، که عربیدان نبودند، از آن بهره ببرند؛ و بدین وسیله خدمتی بزرگ در حق زبان فارسی و فارسینویسی کرده شد.

اشاره به دانشنامهٔ علایی، در کنشنامه، از جهتی دیگر هم حائزِ اهمیت است. چنان که میدانیم، ابوعلی سینا از بزرگترین فیلسوفانِ مشایی و ادامهدهندهٔ راهِ ارسطو حکیمِ یونانیاست. حکمتِ مشاء بوعلی بعدها از طریق ترجمه به اروپا راه یافت و بر فیلسوفانِ مکتبِ اسکولاستیک، همچون آلبرت کبیر و توماس آکویینی، تأثیرِ بسزا گذاشت. طرفه آنکه، فیلسوف و اقتصاددانِ بزرگ مکتب اتریش، موری راتبارد، خود از توماس آکویینی تأثیر پذیرفتهاست، و در سبک و سیاق فلسفی کاملاً ارسطویی عمل میکند؛ و این شیوهٔ ارسطویی وی در چارچوب حکمت مشاء خوش مینشیند. نویسندهٔ کنشنامه با آگاهی از این امر، در دیباچهٔ کتاب نخست به پیروی از شیخالرئیس در دانشنامهٔ علایی، حکمت را به دو شاخهٔ نظری و عملی تقسیم میکند، و سپس دستهبندی راتبراد از علوم مربوط به کنش را چاشنی آن میکند.

نویسنده علاوه بر تفهیم و دانشنامهٔ علایی، به رسالههای فارسی شاگردان شیخ الرئیس چون شرح حی بن یقظان، و همچنین به اخلاق ناصری خواجه نصیر و نیز آثار بابا افضل کاشی، کیمیای سعادت غزالی، آثار فارسی ناصرخسرو، آثار محمد بن ایوب حاسب طبری، آثار فارسی فخر رازی، کشفالمحجوب سجستانی، تاریخ بیهقی، حدودالعالم، تحریرهای داستانهای عامیانه چون دارابنامهٔ طرسوسی (به سبب کاربرد مثال مهراسب در جزیره) و حتی ترجمهها و تفسیرهای قرآن توجه داشتهاست.

امید است که فارسیزبانان و دوستدارانِ علم از مطالعهٔ این کتاب لذت و بهرهٔ درخور ببرند.

ساکنان ایران و دیگر کسانی که دسترسی به خدمات مالی پیپل ندارند میتوانند نسخهٔ دیجیتالی کتاب را از اینجا رایگان دریافت کنند.